Hugh Grant: Fear of the Dark

Exploring fear, horror, satire, and the sinister charm of Heretic’s Mr. Reed.

I’m sure you know him from his romantic comedies. After all, the rom-com genre of the late 90s and early 2000s was practically owned by the quirky, socially awkward, yet oh-so-handsome Englishman we’ll meet today. With heartwarming classics like Notting Hill (1999), Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), and Love Actually (2003), he made women everywhere (and not a few men, too!) a little dewy-eyed.

He is, of course, Hugh Grant!

Grant’s career has had its ups and downs since his rom-com days, but now he’s back with a vengeance, delivering a slew of quirky roles that made me—the genre film nerd that I am—sit up and pay attention.

From his “Wait, is that Hugh Grant? No way!” appearances (yes, plural) in the underrated but fantastic Cloud Atlas (2012), to his role as a hilarious rogue and villain in the equally excellent Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves (2023), and even as an exiled Oompa Loompa in Wonka (2023), Grant is back, leaning fully into the quirky and the downright mad.

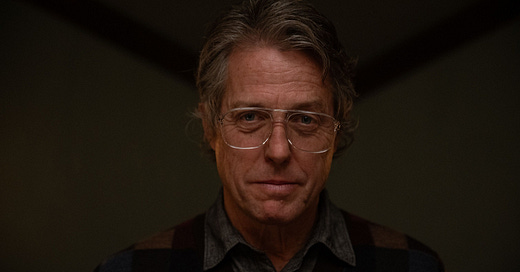

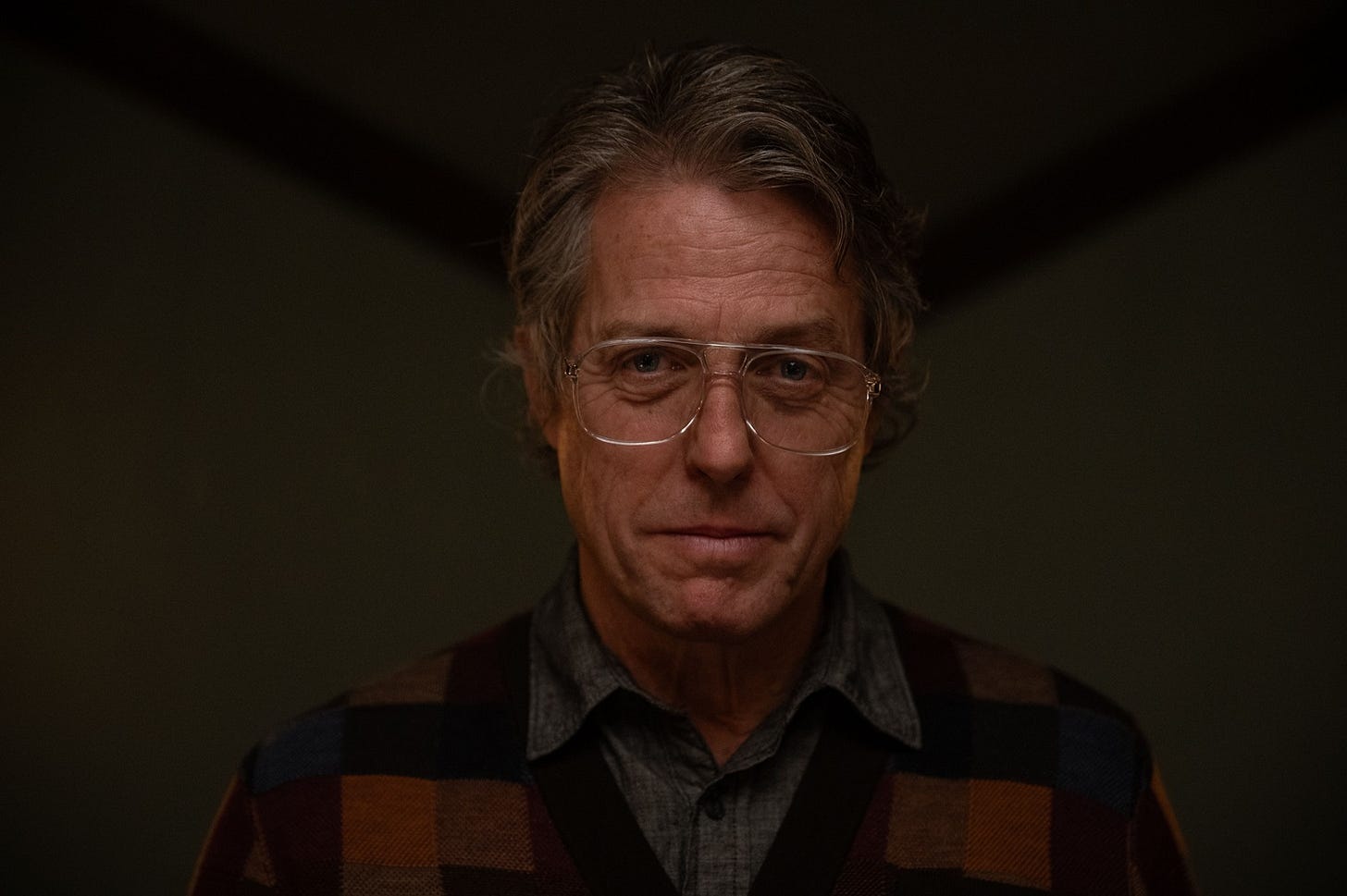

And perhaps no role he has played has been more sinister—or more mad—than Mr. Reed in Scott Beck and Bryan Woods’ philosophical horror comedy, Heretic (2024).

At the tail end of 2024, I joined a small group of fellow Golden Globes journalists for a Zoom conversation with Grant about his chilling role as Mr. Reed, which earned him a nomination for our award.

Before we continue, this interview contains spoilers for Heretic. Or, as Hugh Grant said in our Zoom call: “Well, yeah. All right, fuck it. Everyone’s seen it or they’re never going to see it now.”

Accepting the Role

Hugh Grant described his decision to take on the role of Mr. Reed in Heretic as unusually straightforward. “It was, I think, especially for me, a relatively easy yes,” he admitted. “I like to agonize over these things, and I like to create agony in the people who’ve kindly offered me parts. But in this one, I feel like I instantly had an inkling that I could have some fun with him.”

He talked about what drew him to the character: “I mean, I like dark and evil and twisted and screwed up anyway. And then I thought I saw a way for this guy to be, to think that he’s fun and down with the kids—funny even. Even if he’s kind of not funny. And I thought that could be really weird. Enjoyably weird.”

Grant also praised the creative team and the studio behind the film. “I thought these two writer-directors, Scott and Brian, were very interesting. I had loved the film they wrote, A Quiet Place. And then it was A24, and I thought, you know, they’re cool. I’m cool. It’s a perfect match.”

Becoming Mr. Reed

Hugh Grant spoke extensively about the preparation he put into playing Mr. Reed, a process he described as increasingly elaborate over the years. “Well, I think my prep for films for parts has always been the same,” he said. “It’s just become more and more exaggerated and ridiculous as the years have gone on. I always, from the start, did a lot of worrying and a lot of minute examination of motivations, thoughts, feelings, the background biography of the character. Even in those romantic comedies where it seemed like I did no work at all, I did actually.”

He explained that his approach has intensified recently. “It has got worse, especially in the last six or seven years,” Grant said. “For instance, on this one, I mean, the biography of Mr. Reed that I created mushroomed over the many weeks of prep. I mean, it must be 100 pages now. I had labyrinthine little schematics of what Mr. Reed’s plan was for the evening. I think he’s had these little parties before. Sometimes I think his victims escape. While they escape, he lets them go. But I think he’s had a plan that sometimes takes them all the way to that deepest dungeon. So I did try to work out that little plan as well.”

His preparation also included extensive research. “There’s all the sort of research,” he shared. “I researched killers—you know, serial killers, cult leaders, atheists, Richard Dawkins, people like that. So there was a lot of prep.”

Grant found the psychological aspects of the character both challenging and fascinating. “Why is it fun to be someone so cruel? I can’t answer that. But it is,” he said. “Why are actors drawn to these characters, and why are audiences fascinated by them? Often, they prefer them to the good guy in the film. I think it means we’re all basically deeply cruel, vicious beasts with a thin veneer of civilization over us.”

He elaborated further on Mr. Reed’s motivations. “The fact that he gets so much pleasure from disorientating and bewildering and terrifying these girls is sort of deliciously awful,” he admitted. “But I had theories about why he needed to do that. I thought, probably, he had an unhappy history with women where he’d never been very successful. And this is a kind of revenge or compensation—to destabilize them, worry them. Enslave them.”

Although his preparation was detailed, Grant admitted with a wry smile, “A lot of which I’ve now forgotten. A year later, my memory seems to be fading fast.”

Holding Darkness Within

Heretic, being a film about people trapped in a house with someone deeply unpleasant, brought to mind a chilling encounter Hugh Grant had with the supernatural. “Well, I have been in a haunted house. I’ve told this story before—I can’t remember where—but it’s awful,” he began, candidly. “The last thing in the world I want to believe in is ghosts or another dimension. Because I can’t cope with the dimensions we have. But I did, in a very clichéd situation, see a ghost in a castle in the north of England in the middle of the night. Just no question about it. And I was sober.”

He described the encounter in vivid detail. “I said to the owner of the castle the next morning at breakfast, ‘I saw this thing up there. This—it was a colored light on the floor that moved through me and down the corridor and into another bedroom, through the wall.’ And she said, ‘I know. It’s been there for hundreds of years. I think it had a name. It was like the fourth Duchess or something. Something terrible had happened to her.’”

Grant admitted, “Sadly, this unequivocally happened. So I do believe in ghosts, and I’m extremely frightened of them.”

His fears, however, extend beyond ghosts. “I’m very frightened of the devil, too,” he confessed. “I read The Exorcist when I was too young. I remember my mother snatching it out of my hands and tossing it into the bin. I got it out again. I shouldn’t have done that. Anyway, the devil has haunted me in my dreams periodically from that moment to this. About once every two months, he comes for me.”

Grant revealed how these dreams affect him. “Apparently, when I’m having my devil dream, I make a very unmanly noise. My wife tells me I go, ‘Whooo!’” he said, laughing nervously.

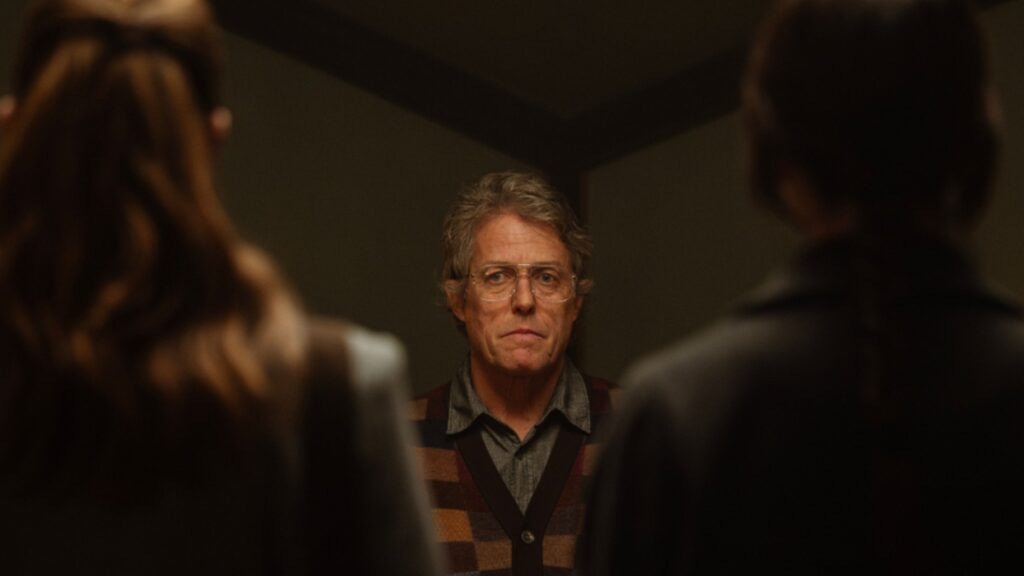

The Joy of Dialogue

Hugh Grant reflected on the differences between acting for screen and the stage, admitting his struggles with quick takes and close-ups. “I don’t cope very well. I never have done with the fragmentary nature of filmmaking,” he admitted. “You’re filming tiny little bits of a scene in any one moment. You know, the lights and cameras are all set up for an hour, and then you’re just going to get half a page. And in a close-up, or worse, just a little reaction—‘We just need to get that bit where you go.’ And I find that extremely difficult.”

By contrast, Grant explained, performing longer sequences is more natural and reminiscent of theater. “Long sequences like you have in the theater are considerably easier. You get into the swing, you have rhythm, you have flow. You can use your whole body. Everything is just much more natural,” he said.

This theatrical approach became possible in Heretic for several reasons. “This film was a unique opportunity to do that while making a film. Partly because of budgetary constraints—we didn’t have an enormous amount of money and therefore time—and partly because there was all this talking,” he explained.

Grant praised Director of Photography Chung Chung-hoon for his work on Heretic. “Chung Chung realized that this would only work if we could do enormously long takes. So whereas in a normal film, if you did a take that was three pages, that would be very long. In this one, we did ten, twelve-page takes. And I guess they wouldn’t have even been possible in the old days with celluloid because no magazine is big enough. But with digital, you can do it.”

For Grant, this style of filmmaking was very rewarding. “Insane and lovely,” he said, describing the experience. “You know, especially if you’ve got wonderfully choreographed camera work. All the actors come into play at some point; they’re on screen. That’s always my experience—it always makes the best scenes when you find a way that all the actors are in the shot. They all try their hardest, and they like playing off each other.”

He compared this collaborative energy with the isolation of close-up shots. “When it’s all split up—‘Okay, you know, it’s your close-up and the other actor is off camera’—the other actor is never really as on it as they were when they were on camera. Or they do something different, and I’m the same. It’s just impossible to have quite the same focus when you’re off camera. Your cup of coffee is calling. You know, we all try not to be like that, but it happens,” he admitted.

Grant further emphasized how this theatrical rhythm influenced his performance. “It’s just more like the theater,” he explained. “Flow, rhythm—I personally think rhythm is incredibly important. Like, you can hear a beat, but people talk about beats in acting. You know, ‘just hold two beats there.’ But actually, I think there is a kind of pulse, and you’re playing with it all the time. So if you suddenly stop, it means something. And if you go faster, it means something. But when you’re shooting tiny little fragments, it’s very hard to hear the pulse.”

Funny Guy

Hugh Grant talked about his approach to playing Mr. Reed, focusing on the importance of the character’s self-perception as amusing. “I always thought that the way into this character for me anyway, if I was going to do it, was that he should think he’s quite amusing as well as fascinating and iconoclastic and all those things,” he explained. “His shtick in these scenes is the shtick he’s been doing as a teacher in universities, where he’s the funny guy who comes in and surprises them by making references to Jar Jar Binks or, you know, Radiohead.”

He admitted to pushing the character’s humor even further to enhance the contrast between Mr. Reed’s wit and the film’s darker tones. “I personally pushed it all to try and extend it a bit more. And, you know, make it even more jokey, more silly,” he said. “So that when I’m introducing Monopoly and I say, ‘Here are all the avatars, everyone has their favorite. I’m not telling you mine,’ this was all me trying to push at the idea that he thinks he’s a funny character and also to make him enjoyable.”

Grant acknowledged the challenge of keeping the character’s lengthy monologues engaging. “There is a danger—I always thought there was a danger—if you’ve got enormously long, speechifying lectures, that the whole thing could get quite dry,” he explained. “So I thought, he has to at least think he’s amusing, even if we’re thinking, ‘That’s not funny. What’s he doing? He’s so ghastly.’ But I thought that would be enjoyable in itself and actually would make the horror more horrible because of the odd contrast.”

As for whether he enjoyed making the film, Grant was candid. “Oddly enough, you know, I hate my job. I’ve said that many times because I’m so nervous and worried that it’s going to go wrong, or that I’m going to be attacked by a sudden panic—a panic freeze—because that usually comes for me once or twice in a shoot,” he admitted. “I’m in a permanent state of terror about that, which puts a cloud over me and over the whole set, I may say.”

However, he expressed his genuine admiration for the people he worked with on Heretic. “I did love the people who I made this film with. Genuinely,” he said. “Those girls are sensational. Sensational actresses. They’re lovely people. They’re funny, they’re interesting. I liked my two weirdo directors very much. And the Vancouver crew were exceptional. They were so supportive. I mean, I’ve never been on a film set before where, at the end of the day, one of the big scary grips comes up and says, ‘That was great.’ You know, they’re so encouraging. So I can almost say I did have some fun.”

Rom-com vs Horror

Hugh Grant discussed the transition from his iconic romantic comedy roles to playing darker characters like Mr. Reed in Heretic. “Honestly, I never thought of it as the same charm,” he said. “I thought he was a completely different beast. I thought he was—as I keep saying—he thinks he’s amusing and kind of charismatic. But quite quickly, everyone throughout his life has thought, ‘There’s something wrong with you. Back away.’”

Grant admitted to leaning briefly on his signature charm in one pivotal moment. “The only time where I perhaps put the weight on the foot of unadulterated, genial, warm charm was right at the beginning when I answered the door,” he explained. “Simply because we couldn’t have a cinema audience think these girls are idiots to go in there. So I really had to lean on that there. But after that, I hope that what I’m doing is a kind of painted-on charm that we realize is painted on, and there’s something cooking underneath. Something not very nice.”

Reflecting on the evolution of his career, Grant clarified that his shift to darker roles wasn’t sudden. “It’s not like I suddenly went from the romantic comedy guy to this. You know, I haven’t really been nice in a film for about ten years,” he noted. “They’ve all been various forms of freak or monster or weirdo or even killer. If you think about The Undoing, the miniseries I did with Nicole.”

When asked why he’s embraced playing unusual or villainous characters over the past decade, Grant didn’t mince words. “It’s partly because that’s what I get offered now. Now that I’ve got a face like a smacked bottom,” he joked. “And now that I’ve gone back to where I started. Really. When I started out acting, if someone had said to me, ‘What are you good at?’ I’d have said, ‘Well, weirdos. I mean, characters.’ As a kid, I couldn’t stop doing characters. People would say, ‘Stop, just be you.’ And I’d say, ‘I think, I don’t know how to do that.’”

Ultimately, Grant expressed satisfaction with the roles he’s taken on in recent years. “So I’m much happier in the last eight years, creating people who I think are completely unrelated to me,” he said, admitting his comfort with leaving the romantic comedy archetype far behind.

Embracing Fiction

Hugh Grant shared his complicated relationship with horror films, admitting that his fear of the supernatural has shaped his perspective. “I struggle with them because of my terror of the devil and evil spirits, so I can’t say I’m an expert in them,” he confessed. “The Exorcist—I did see the film. I don’t think if you sat me down with it now on this laptop, I would be able to watch it. It’s too much for me. Oh, God. When she comes in and pees on the floor. When her head spins around.”

Despite this unease, Grant expressed his appreciation for the genre’s cinematic potential. “I am aware of how the horror genre can often bring out the very best in cinema and in the art of cinema,” he said. “If you look at Hitchcock or you look at Kubrick—The Shining—bits of Polanski, these guys, what they’re doing is pure cinema. I always think cinema should take you somewhere where you never get to go in real life. You know, you’ve got TV for, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s like life.’ Cinema should take you somewhere where you go, ‘Oh, God, we’re not normally allowed here.’ It should be bigger. Weirder. Sometimes sexier, sometimes more violent, sometimes more horrible. But more than real life. It should be a fairground ride. And I can see that horror ticks that box and is a gift to the gifted filmmakers.”

When the topic shifted to the use of horror as a vehicle for social commentary, Grant made his disdain for overt messaging in fiction clear. “I suppose so. I hate messages,” he stated bluntly. “I don’t think films or books—or when I say books, I mean novels or anything fictional—should ever have a message. If you want to tell someone a message or make a point—a political, social, whatever point—you know there are many other mediums to do that in.”

For Grant, creative storytelling is about artistry, not instruction. “I think that creative storytelling should just be that. It should just be creative, and it just should sit there,” he explained. “As soon as any filmmaker or author starts to say, ‘This is the message I was trying to say,’ I think they’re a filmmaker and a shit author. That’s what I think.”

And there we have it—the quirky, hilarious, and slightly neurotic Hugh Grant, sharing his thoughts on bringing the sinister Mr. Reed to life in Heretic. As the interview wrapped up, Hugh, being quintessentially Hugh and visibly uncomfortable with Zoom, asked, “What button do I press?” before the screen abruptly went black.

Never change, Hugh!